‘The Jaws Myth’

It’s unlikely that any film about an animal has had such a lasting cultural impact as the 1975 summer blockbuster, Jaws. Neither has a starring animal- the shark, or more specifically, the great white shark- ever been so strongly associated with, and defined by, a single film. From the instantly recognizable ‘duh-dum, duh-dum’ music score, to the ‘you’re gonna need a bigger boat’ line, many people’s first introduction and main reference point to sharks comes from Steven Spielberg’s classic. Yet the film’s legacy has faced growing scrutiny due to its apparent vilification of creatures, which are in reality far from the vengeful monsters they’re portrayed as on the big screen. Many shark scientists, like former head of the International Shark Attack File, George Burgess, believe the false portrayal greatly damaged the reputation of these marine predators, causing people to develop a fear of them- and that this has led to the decimation of their population in recent decades. Even the author of the book the film was based on, Peter Benchley, admitted he wished he’d never written it due to these perceived negative effects and devoted his later life to protecting sharks. Today this viewpoint on the destructive role of Jaws continues to be echoed in almost any discussion about the movie and shark conservation, and has become something of a truism. However, on closer inspection it becomes clear that this notion is at best a gross exaggeration, based on very little supporting evidence. Let us call this ‘The Jaws Myth’.

‘Bruce’, the 25 foot long mechanical villain of the film Jaws.

So of the approx. 100 million sharks killed each year by human activities, how many of them can be attributed to fear or hatred of sharks? Far and away the most lethal of these activities is the shark fin trade, which results in at least 73 million of those deaths and possibly more. This mutilation and killing is clearly driven by economic factors, with the huge demand for shark-fin soup- a delicacy in China- offering rich rewards. As is clear from the billions of chickens and pigs killed for food annually, being cute or harmless awards an animal no protection from market demand for your meat. To suggest that the shark finning industry would be any less rampant if the creatures they target had a sweeter reputation is simply a claim that doesn’t hold water and denies the true motivations and incentives behind it. This is further compounded by the fact that Jaws has little or no cultural value amongst the populations predominantly involved in the consumption and production of shark-fin soup.

Shark-fin soup is a coveted dish but comes at a high price- in every sense.

Alongside finning, what are the other main reasons for the devastation of shark populations globally? If you may be under the impression that it is one or more of the following- shark nets, lethal drum lines, or targeted culling of dangerous sharks- then the reality is far removed. While these shark mitigation measures cause the deaths of thousands of sharks globally- as well as those of many more marine creatures- the scale of their threat to sharks is a mere drop in the ocean when compared to the overall 100 million annual death toll. Though nets are involved, it is not the beach nets deployed in a handful of coastlines around the world that are overwhelmingly to blame, but the nets and lines of trawlers. As well as the targeted hunt for their fins, meat, livers, skin and cartilage, sharks are also caught in their millions as accidental bycatch. In unregulated areas of the Pacific Ocean, where 70% of the world’s tuna is fished, baited nets are set to catch these fish- some up to 160km long- and which in some instances catch even more sharks than tuna. This detrimental side effect of industrial-scale fishing has no discernable connection to Jaws or any other negative depiction of sharks, yet it is leading the charge when it comes to pushing many species towards endangerment or extinction, dwarfing the negative impact of activities like sport or recreational fishing. Noteworthy conservationists like Valerie Taylor, for example in her acclaimed 2021 documentary Playing With Sharks, speak out strongly against shark nets and advocate broadly for conservation and ecology, but rarely if ever get into the tougher questions of the place of fish and seafood in our diets or managing employment in fisheries while the oceans are emptying.

Sharks are often caught and killed as the unintended targets of fishing trawlers.

If Jaws really has had such a direct catastrophic impact on the shark family and its more than 500 species, you might expect that the film’s appointed villain- the great white shark- would be the most heavily affected. While some statistics have appeared to suggest this, the 79% reduction in their numbers between 1986 and 2000 in the Northwest Atlantic is not as straightforward as it seems. In the same study, there was, for instance, an 89% reduction in the far more benign hammerhead sharks. Sport and recreational fishing in the wake of Jaws on the US east coast has been apportioned an entirely outsized share of the blame, overlooking other regional factors behind white shark population trends. Crucially, the seal population steadily recovering over the past five decades- from fifty gray seals off Maine in 1972 to tens of thousands today- has allowed for a similar recovery in their primary predator’s numbers, especially since the turn of the century. On a wider scale, the 79% decline also reflects a general, stark decline across hundreds of large animal species, from the 1960s to the end of the century. Increasing human populations, pollution, ecological neglect, and many other factors have influenced this downward trend. Sharks, and great whites in particular, reach sexual maturity late and breed relatively infrequently when they do, therefore being particularly vulnerable to a fall in population. So while it is true that their numbers have broadly declined since the ‘70s and the release of Spielberg’s film, this has been a victim of correlation mistaken for causation.

Relentless hunting of grey seals in the Northwest Atlantic deprived great whites of their prey until their numbers gradually recovered

Going back to the plight of the great white shark, contrary to what might be expected, it is perhaps the species most cherished by humans. In spite of being involved in both the most shark fatalities and shark attacks since records began, this phenomenal species has enjoyed more protections and attention than any other member of its kin. When in 1994 California introduced shark protection laws, they were not for the sake of the gentle leopard shark or brown smooth-hound. The state decided to ban the catching of baby white sharks, only 19 years after Jaws. These laws have been broadened and extended in many places around the world to protect the apex predator, both young and old. In many jurisdictions, such as South Australia, activities such as the sale of their teeth or jaws are even prohibited- protections rarely afforded to the hundreds of far less ‘scary’ and ‘notorious’ sharks in our oceans. In some regions of the world like the east and west coast of the US, white shark populations appear to be rebounding as a result of such conservation efforts. White sharks remain listed as ‘vulnerable’, under threat in other regions like South Africa, but their position is privileged compared to many other shark species and this fact throws more doubt on the assumption that fear or danger is a major factor in how we treat or prioritize sharks generally.

Despite posing no threat to humans, eating only zooplankton, the basking shark is now listed as ‘endangered’.

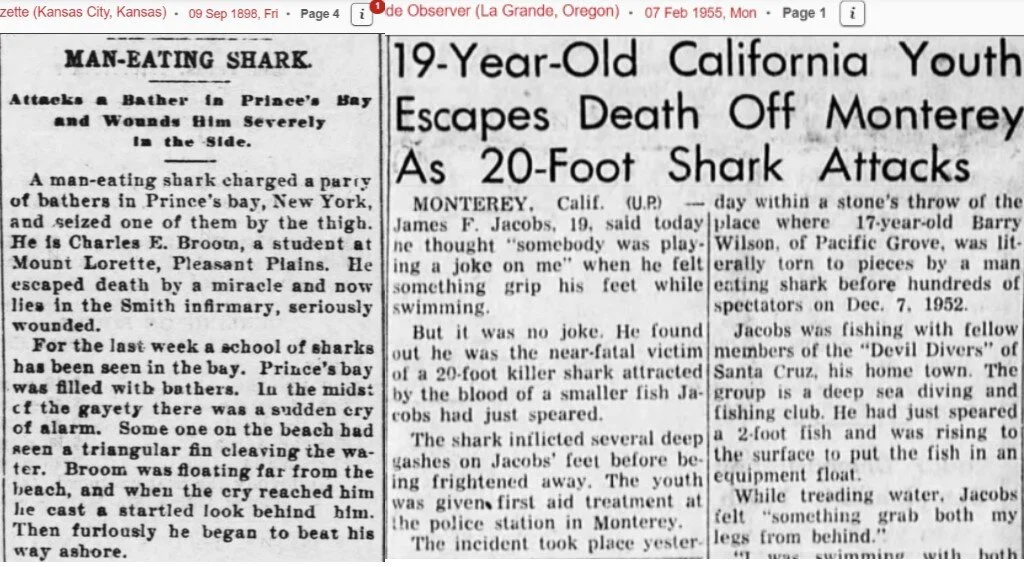

One final component of ‘The Jaws Myth’ is the allegation that the film created fear of sharks almost out of thin air and hardened hearts against them. While it can’t be denied that many people have been truly terrified by the film- and some have retained those fearful feelings, even avoiding swimming in the sea at all- the bigger picture is far more complex. The impression put forward, that before its release there was merely a general indifference towards sharks, is undermined by even a cursory look at newspaper archives from preceding decades. In 1955, articles from across the US press detailed a near-fatal encounter in California involving a ‘killer shark’, and made reference to another incident three years previously, when a teenage boy was ‘torn to pieces by a man-eating shark’. Countless mentions of ‘shark-infested waters’, ‘monster sharks’ and ‘terrifying/horrifying/appalling beasts’ can be found for many decades before Jaws, further underlining already existing fear and sensationalism around these creatures.

Occasionally the origin point of shark fever is pushed further back, to 1916 and the events that inspired Peter Benchley to write his bestselling novel decades later. That spate of shark attacks in New Jersey is marked out as the beginning in a 2020 National Geographic mini-documentary called ‘Where our Fear of Sharks came from’. But again, just a quick dip into the archives shows a headline in the Kansas City Gazette from 1898 reporting ‘Man-Eating shark attacks a bather’. Or take the 1888 poem by Moby Dick author Herman Melville, 'The Maldive Shark', where he describes the 'ghastly flank' of this 'pale ravener of horrible meat' or 'The Shark' (1897) by Lord Alfred Douglas that tells readers 'After this warning you will wish, To keep clear of this treacherous fish'. Going all the way back to Ancient Greece, the 3rd century lyric poet Leonidas of Tarentum wrote from the horrific perspective of a shark attack victim, a diver named Tharsys - 'I was eaten; so terrible and great a monster of the deep came and gulped me down as far as the navel', and so the diver was 'buried both on land and in the sea'. In spite of the low statistical likelihood of ever being bitten by a shark, human fear often inhabits a far more primal realm and it’s clear the broader historical record definitively reflects that the fear and sense of horror surrounding being eaten by sharks is nothing new. It has likely existed for as long as humans have been wading into the unknown, unseen territory of the ocean.

Historical newspaper articles show that fear and dramatic coverage of sharks is nothing new.

One strangely paradoxical legacy of Jaws has been the legions of shark lovers it has spawned. For many a conservationist, biologist or amateur enthusiast, the book or the film served as their gateway to the world of sharks, and although the unrealistic and dramatized behavior of its protagonist now seems laughable, the film helped create a considerable awareness and interest. Regrettably, the good intentions of many of these same people to defend sharks has given rise to ‘The Jaws Myth’, a convenient scapegoat for the vast, knotty and dire situation these animals are facing. But if it is only a fiction, what harm could it do? In truth, quite a lot. ‘The Jaws Myth’, however well-intentioned, serves as a harmful smokescreen. Undoubtedly it makes a compelling and sexy theory that can be worn virtuously by its proponents and easily, eagerly consumed by an audience, but ultimately, it only obscures the main issues driving sharks towards extinction. The key to ensuring their continued existence depends not so much on challenging fears as on challenging ignorance and greed. So why won’t this myth- like the fictional man-eating shark trying to sink your boat- just die already?